Paul Simon wrote a song in 1975 called “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover,” but, when dealing with process improvement, there are really only “5 Ways to Improve a Process.” It is all about reducing variation; whether it’s variation in time to serve a customer at the Bahama Bistro, variation in dimensional values of a product – the amount of meat placed on a sandwich order, variation in the quality of a service – server’s knowledge of the menu items or variation in costs associated with the meal (including the labor and materials) itself. It’s all about variation.

In his book, Quality Management for Organizations Using Lean Six Sigma Techniques, Dr. Erick Jones defines Lean Six Sigma as “the relentless pursuit of process variation reduction and breakthrough improvements that impact customer satisfaction and impact the bottom line.” I like this definition. It implies an ongoing journey, not a single project. Improving processes becomes a personal mindset – “are there ways to do this better?” Will reducing the variation in this process provide a benefit to the customer?

Improving processes becomes a personal mindset – “are there ways to do this better?”

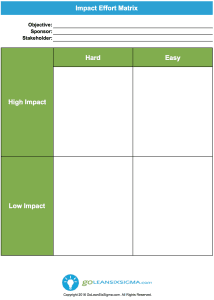

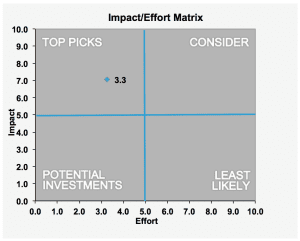

With so many processes within an organization, and each one with potential improvements, the first dilemma is, “where to start?” Make it easy on yourself. Pick a process where you are managing or participating and ask, “how am I going to improve this?” “What variation currently exists in my process?”

The “5 Ways”

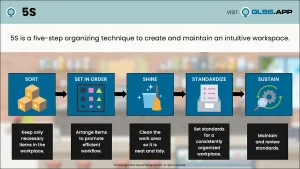

This is where the “5 Ways” come into play. In my experience, the ways to improve an existing process are limited to these 5 categories:

- Reduce Non-Value-Added Steps

- Improve the Measurement System

- Reduce Common Cause Variation

- Reduce Special Cause Variation

- Move the Mean to Improve Process Capability

That’s it. The key is to know which type of improvement you are bringing to the effort. Let’s clarify the “5 Ways to Improve Your Process.”

1. Reduce Non-Value-Added Steps

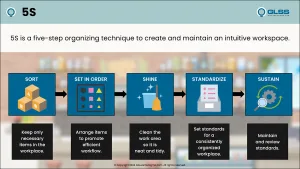

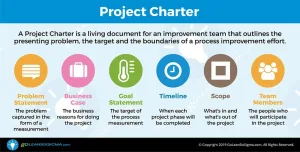

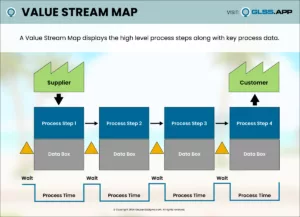

Every process consists of a series of steps which are initially listed in the SIPOC. But a high-level view is not sufficient to truly understand the process.

The first requirement is to build understanding of how a process works. Not how it’s is said to work or documented to work, but how it actually works. “What do the people within the process really do?” Conducting a Process Walk or just spending time with process participants to document the process such that people (especially those within the process) can see the “big picture” generally produces some easily achievable results or Quick Wins.

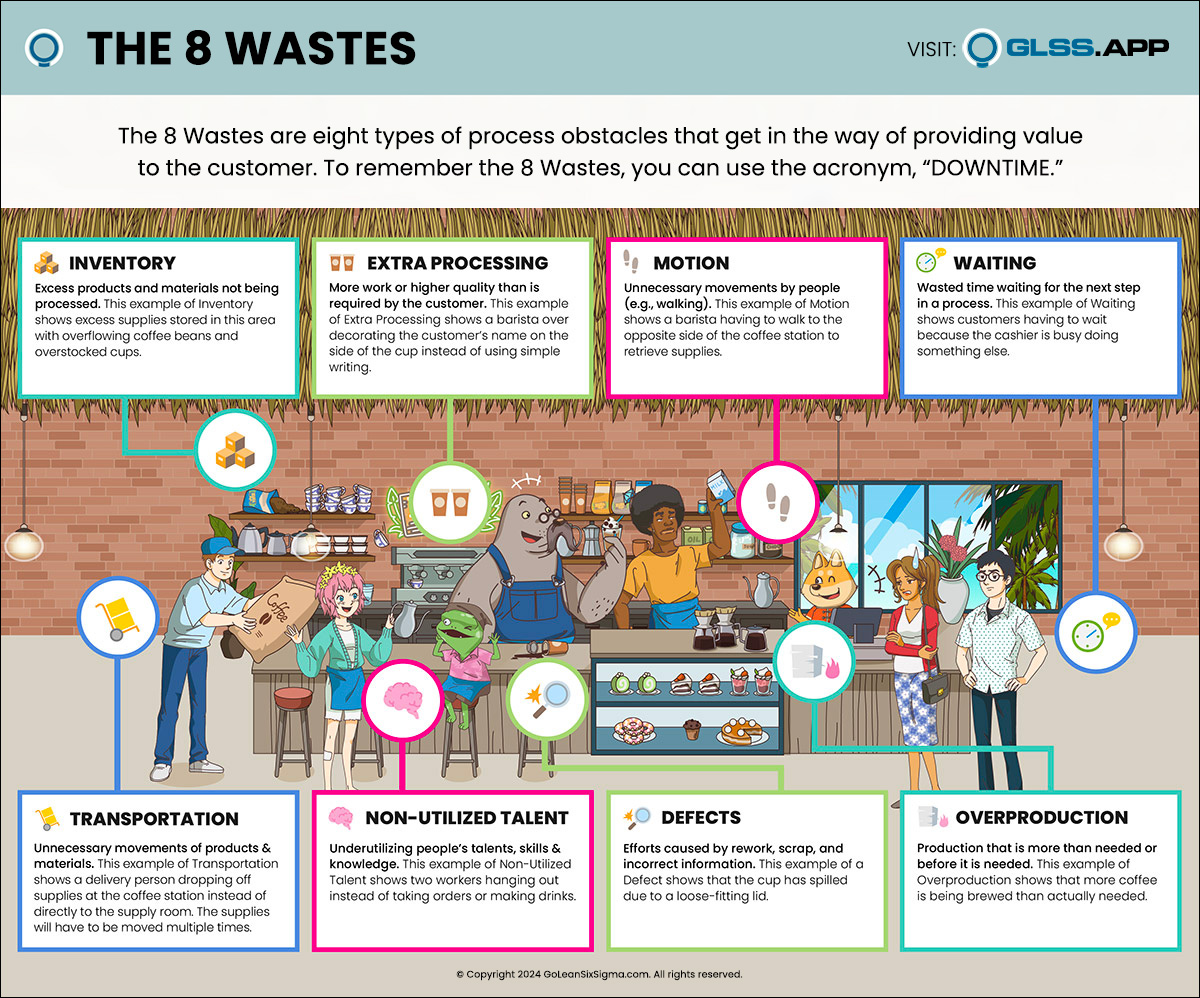

Look for bottlenecks in the process and seek ways to balance the workload. Identify the non-value-added steps and determine if they can be eliminated. Are you able to bring the value-added steps together in a manner that benefits the customer? Every process has waste. Your job is to identify, reduce or even eliminate it.

Consider the following process. You are assigned to assemble and mail 500 envelopes to your customers. You have 3 colleagues who have volunteered to assist. Typically people organize themselves into an assembly line for this activity, similar to the Swimlane Map shown.

But if you examine this process, there are a number of non-value added steps. Every movement to and from each stack is non-value-added. Furthermore, folding takes the most time and therefore forms a bottleneck in the process.

Eliminating these non-value-added steps is relatively easy. Simply have each of the four people do all of the steps rather than handing it off 3 times. This eliminates all of the moves and pick ups. With the bottleneck distributed across all 4 people the task takes much less time.

Simplifying the process by looking for waste in the process is a good place to begin any improvement effort, because it is easily understood by those working in the process and doesn’t require a lot of data collection to implement improvements.

2. Improve the Measurement System

Whenever you collect data, the variation you observe is a combination of the variation in the process and the variation in the measurement system.

Every measurement system has variation, but often those pursuing process improvement forget to evaluate how much of the variation is a result of the way it’s being measured. Measurement variation is linked to the clarity of the operational definitions for each measure.

No operational definition is perfect. There is always some “interpretation,” whether it’s how the measurement device is read, the effectiveness of the scale on the device or even what the operator does with the data once the reading is made. Consider a recipe that calls for “a spoonful” of sugar. How much is that – a teaspoon? A tablespoon? A heaping tablespoon? Lots of room for interpretation there.

By examining how people behave when given an operational definition, in this case, “a spoonful,” we can measure the difference in their interpretations. In many cases, the variation is relatively small but, surprisingly, there are many times when it’s big. Unless you check, you will never know.

In many cases, the variation is relatively small but, surprisingly, there are many times when it’s big.

I have seen many companies fail to recognize reduction of measurement variation as a “valid” improvement project. But if reduction of variation is a goal of Lean Six Sigma, then this certainly fits the bill. I promise, the results are worth the effort.

3. Reduce Common Cause Variation

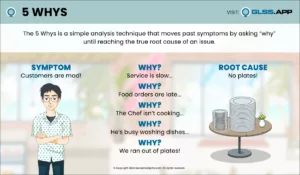

It is an underlying principle that variation exists in all processes. Dr. Walter Shewhart and Dr. W. Edwards Deming espoused that variation could be broken into two classes, common and special causes.

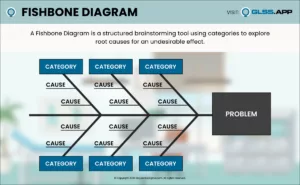

The separation of these two classes is related to how frequently each type of variation is observed in the process. Common cause variation is present on a “regular basis.” It is part of the existing process and traditionally labeled using a Cause and Effect Diagram (aka Fishbone Diagram) arranged with the input (or major bone) categories:

- manpower

- machine

- methods

- materials

- measurement

- environment

To reduce this kind of variation you must stratify your data to determine the amount of variation attributed to each factor. Stratification factors include things like location of the process, early or late shift, day of the week or type of order. The idea is to look for significant differences in the process outputs when these factors are present.

We’ll use the the meal preparation process as an example. The Control Chart above shows common cause variation, but when stratified by meal type, you find two different distributions in the data.

Knowing this difference provides a better opportunity to examine the variation in the salad preparation separately from the sandwich preparation. Since sandwiches take a lot longer that’s a good place to start.

Design of Experiments is one way to gather this information, although it requires you to actively engage in changing the process rather than just passively observing it.

However, once you have this information, you can pursue ways to reduce this variation. In many cases, this involves working with suppliers, whether they are internal or external to your organization, to assist them in reducing the variation in their processes. Of the “5 Ways,” reducing common cause variation is the most difficult.

4. Reduce Special Cause Variation

A process which only contains common cause variation is considered stable or “in control.” This means the amount of variation in the process is consistent and predictable.

In contrast, special cause variation causes processes to change. The change might have a positive impact on the process, or it may be negative. Recognizing the change provides an opportunity to understand why it changed. Once the root cause is understood, the information can be used to benefit the customer.

Special cause variation includes:

- A specific unique change – a single point outside the control limits (aka outlier), such as traffic accidents during a snowstorm

- A shift in the process to a different level of performance, such as a sudden shift in the number of delayed meal deliveries due to a new untrained cook being added to the staff

- A trend, a more gradual change in the process over time, such as a steady increase in a person’s weight

Eliminating special cause variation results in a more consistent process as well as an overall reduction in variation. The key is recognizing when a change has occurred. Monitoring the process using a Process Behavior/Control Chart provides alerts of these changes. This enables a team to analyze why the change occurred.

Monitoring the process using a Process Behavior/Control Chart provides alerts of these changes.

5. Move the Mean to Improve Process Capability

The focus of the first 4 Ways is on variation, but we live in a world that require specifications. Since process variation can be excessive, organizations establish specification limits to narrow the variability experienced by the customer.

Items that fall within specifications are deemed “good,” and items falling outside the limits are reworked or scrapped. The capability of the process is defined as the ability to deliver outputs that are within the specifications.

Even if the variation is large, if the mean is not centered within the two specifications, the amount of rework will be larger as more values fall out on one side versus the other. In this case, the mean is at 54.75 instead of 55, which results in 28% rework. Even without reducing the variation, moving the mean to 55.0 will reduce the amount of rework to 18%.

Understanding which of the “5 Ways” to use to when improving a process helps focus an improvement effort. Start your improvement efforts by picking one of the “5 Ways” and using it to make an initial improvement. Celebrate your success, make sure the improvement can be sustained and then either look for another way to improve this process, or choose another process to work on. It can really be that simple!

Improvement efforts should be ongoing – one step at a time, a relentless pursuit of variation reduction that improves customer satisfaction and/or increases the bottom line.

Do you have a favorite improvement method? Do you find yourself using one of the “5 Ways” over others? Tell us about it!