“Gemba” is a Japanese word that translates into “the site” or “the place of work.” There is a related word, “Gembutsu” which means the “actual thing.” We “go to the Gemba” to find out what is really happening.

That might be a nice piece of philosophy, but what does it have to do with improvement? As facilitators of improvement, we often have problems to solve, and need to quickly assess the facts of the situation in our search for root causes. For those of you familiar with the Process Walk – it is one type of Gemba, but depending upon the problem you may not need to walk the entire process – or you might have to walk several of them.

Fact vs. Fiction

As problem solvers, we often have much more information than we need and must sift through it all to find not only the relevant information, but to separate fact from fiction. When we begin our quest to solve a problem, we will often talk to knowledgeable people to get background on the situation. Sadly, it is amazingly common for those people to give us information that may be misleading or simply untrue.

If they truly understood what was causing the problem, chances are that your help wouldn’t be needed.

I’m not suggesting any malicious intent, but rather that the people you talk to may be blinded by “honest wrong beliefs.” If they truly understood what was causing the problem, chances are that your help wouldn’t be needed. There are often unique attributes to the situation that may defy an easy solution by those close to the process.

As an independent problem solver, you can bring two essential qualities: objectivity and ignorance. You can be objective only if you are not corrupted by the honest but wrong beliefs of those close to the process. As an “outsider” to the process, your initial ignorance gives you a “blank slate” that may allow you to see past the “honest wrong beliefs.”

Reason 1: There’s No Substitution for Observing the Process in Person

I was working with a company who made earthmoving equipment. I helped them implement Six Sigma by coaching some of their Black Belt candidates. I was approached by a candidate for a second opinion – he didn’t like the advice he received from his assigned coach. The Black Belt candidate was stationed at the home office, while the problem was in a remote plant, reachable only after an arduous journey. In addition, he was newly married and would rather spend evenings with his wife at home than in a remote motel. He advocated conducting the project entirely by conference call, avoiding the plant visit. Now I’ve been at this for quite awhile, but I still remember what it is like to be a newly-wed; still, I advised him to go to the plant and see for himself.

He was trying to remedy an extremely serious problem: the plant was shipping half their orders late! The plant manufactured hydraulic fittings and was causing delays at other plants. The candidate thought it was a terrible project because he would have to deal with a lot of “poor performers”, but I assured him that he was very fortunate to have such a great first project. Why? The problem was so bad that someone’s job was in danger, so there would be great desire to fix the problem. Besides, performance was so bad that the problem was likely to improve all by itself.

Once we got past these preliminaries, I advised him to go to the plant, observe the operations and test the information he had been given. The leading reason claimed for the late shipments was that there were a number of urgent orders that required shipment in less than standard lead times. My disappointed, newly-wed traveled to the plant and quickly discovered that there were indeed urgent orders, but they accounted for less than 10% of the late shipments. This meant that most of the late shipments were the result of something else.

My disappointed, newly-wed traveled to the plant and quickly discovered that there were indeed urgent orders, but they accounted for less than 10% of the late shipments

I won’t get into the entire diagnostic journey, but the Black Belt candidate discovered by being there that most of the late shipments were the result of actions taken at the plant, inadvertently causing the very problem they were trying to solve. I won’t claim that going to the Gemba was what solved the problem, but it certainly helped.

If you are reluctant to go to the Gemba I urge you to reconsider. You might have been told quite a story by the insiders, but the Gemba will allow you to see for yourself what is happening. Even a beginning problem solver can learn much by simple observation.

Reason 2: Bust Every Assumption

In another instance, I was called into a plant to solve a capacity problem. I listened patiently while they explained that the “Cold Presses” were the constraint, and that lately Scheduling had been giving them small loads to produce, which wasted capacity and slowed the process. After a time I had heard enough, and asked to see the Cold Presses. I was taken to the shop where I saw eight Cold Presses, half of which were idle. I asked why these critical resources were not working, and was told they would be operating soon. After half an hour, loads moved in and out of the presses, but most of the time half were idle. My associates tried to explain that this was unusual. I asked them to track how many loads they produced on each machine for the next day.

We all realized that the Cold Presses were not the constraint, and we proceeded to discover the real constraint and fix the capacity problem.

The following day the data showed that none of the Cold Presses produced as much as they should have. After some discussion, we all realized that the Cold Presses were not the constraint, and we proceeded to discover the real constraint and fix the capacity problem.

Reason 3: Discover the Real Deal

On another occasion I encountered suspiciously “round” numbers. While attempting to streamline a process we encountered an operation which was to run for 30 minutes – a suspiciously round number! When I asked the origin of the 30 minute standard I was first told that it was part of the work instructions, but further digging led to a process engineer who had specified the time. In discussion with the engineer we discovered that the value was determined through “engineering judgment.” Now, if you are not an engineer, engineering judgment sounds rather mysterious, but it’s really just a guess – made by an engineer!

This wasn’t a big improvement, but a six minute savings over thousands of loads a year adds up!

The engineer agreed to some tests and we discovered that the minimum time required to produce a quality result was 22 minutes. We agreed to change the standard to 24 minutes to provide a margin of safety. This wasn’t a big improvement, but a six minute savings over thousands of loads a year adds up!

Reason 4: Simplify the Complexity!

Business can be complicated, unless you force it to be simple.Think about how you would run the process if you were doing it in your garage.

I was asked to work with a shipping manager to resolve a truck loading problem. The plant had four dock doors and had long been requesting additional dock doors. When you drive by a major warehouse or distribution center there are often 50-100 dock doors evident, so four seems like a very small number.

After half an hour of briefing in conference room I suggested that we go to the loading dock. At the dock I saw two trailers pulled into two of the four dock doors, with the other two being empty. There was a small staging area filled with boxes. The loading dock was at the end of the production area and many of the products coming off the line went right into the trailers, while some were set off to the side. When I asked why, I was told that those boxes were for a different customer.

As I watched, I thought that if I were running this operation out of my garage I would want all the product to go right from the production line to the trailer, and then on to the customer. I asked what determined the order product came off the line, and was told it was based on the order in which they were started. After a little discussion we determined that if we scheduled all the product for a certain customer to together, it would come off the line together and could go right onto the trailer. After further discussion with production management we conducted a few trials and soon discovered that four dock doors was more than enough!

Reason 5: Opportunities to Ask

Don’t be afraid to ask what might seem ridiculous – you could be on the right track!

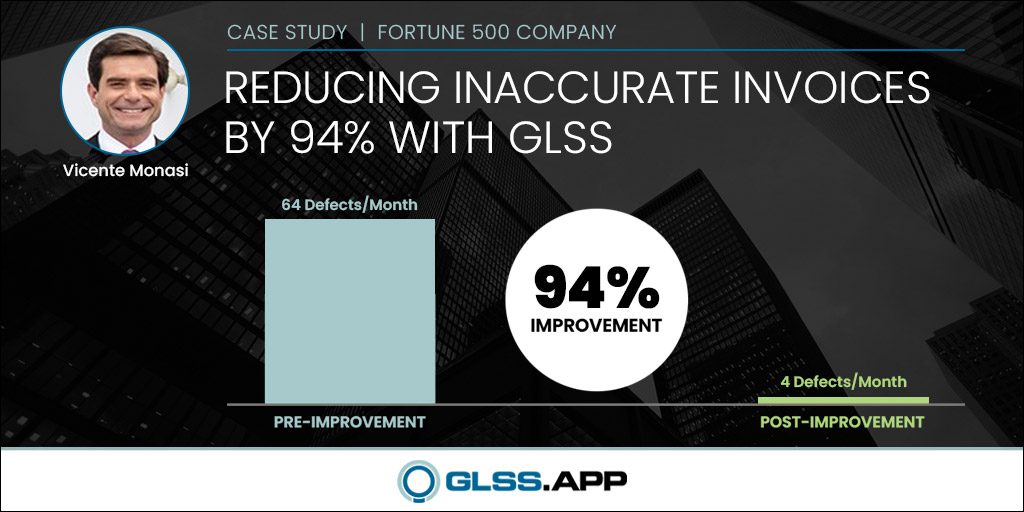

I was working with a service operation for earthmoving equipment. Machines were brought into the shop for repairs. In many ways it was similar to an automobile repair operation at a car dealer. The problem we were attacking was invoice generation, which typically took ten days or more – sometimes several months. The client felt that ten days was an acceptable time, but wanted to reduce the really long times. When an invoice reached a customer several months after the service, the service may not even have been remembered, which led to challenging the invoice, and often negotiating a lower price settlement.

I was struck by how similar the operation was to automobile service and asked the client how long it took them to get an invoice when they brought their car in for service. They smiled and said they not only got the invoice the same day, but had to pay for the service before taking the car!

They were quick to point out that “this is not an auto repair operation – we give our customers 30 days to pay.”

They were quick to point out that “this is not an auto repair operation – we give our customers 30 days to pay.” Even so, why delay giving them the invoice? As a result, they substantially streamlined the process. They never got down to same day invoicing, but they reduced the time to far less than ten days, and nearly eliminated the really late invoices!

6 Tips for Going to Gemba

- Dress for the location – if you are going to the shop floor or a warehouse, dress casually. One of my associates ruined a new pair of dress pants when an adhesive applicator squirted on him

- Keep an open mind and learn – nobody should expect that you know much about the problem – you are there to discover what is not yet known

- Ask lots of questions – if the answers don’t make sense to you, keep asking!

- Ask to see examples of what you have already been told – one solid piece of evidence is worth more than lots of stories

- Question “round” numbers, or numbers that seem to convenient – they may be based on judgments rather than facts

- If you can envision what an “ideal process” might look like, explore what about the “as is”real process is different – if you know of a similar process that runs better, use that as a reference.

Okay, so you’ve decided to go to the Gemba – how much is enough? Unless it is impossible, I suggest that you always go at least in the beginning, and if practical visit from time to time to stay in tune. Believe me, nothing can compare to your actually seeing for yourself!

So, where and when will your next Gemba Walk be?