Across America standardized testing has increased since 2002, when No Child Left Behind legislation was enacted. Thinking broadly on our education system, the question can be posed: Is standardized testing making a difference?

Graduation – it’s that time of year for speeches to impart wisdom on a new generation of graduates. In our local high school, the student commencement speech had a message about individually making a difference with their lives. The student went on to say that their class had already made a difference this year by supporting the “opt out movement” – a demonstration by students and parents choosing to opt out of mandatory standardized testing aligned to the common core standards. Often this is in protest to too many tests taking time away from teaching and learning. Was this student right?

Is Standardized Testing the Problem or the Opportunity?

Across America standardized testing has increased since 2002, when No Child Left Behind legislation was enacted. Thinking broadly on our education system, the question can be posed: Is standardized testing making a difference?

One representation of the problem is that 50% of US colleges and universities remediate their incoming students and yet they generally accept only A and B-level applicants, as quoted in the film documentary Race to Nowhere.

Consider that without a high school diploma you couldn’t work as a garbage collector in Denver and you couldn’t join the Air Force. Yet on average 25% of students do not finish high school. In this era in which knowledge matters more than ever, why do U.S. kids know less than they should?

Yet on average 25% of students do not finish high school.

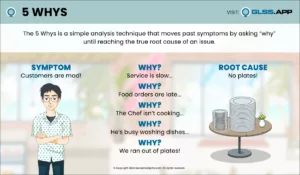

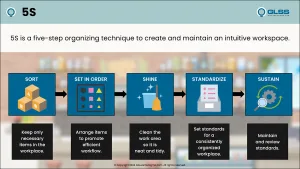

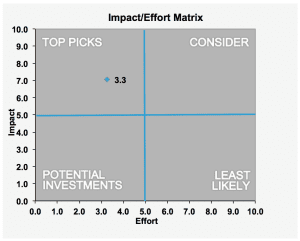

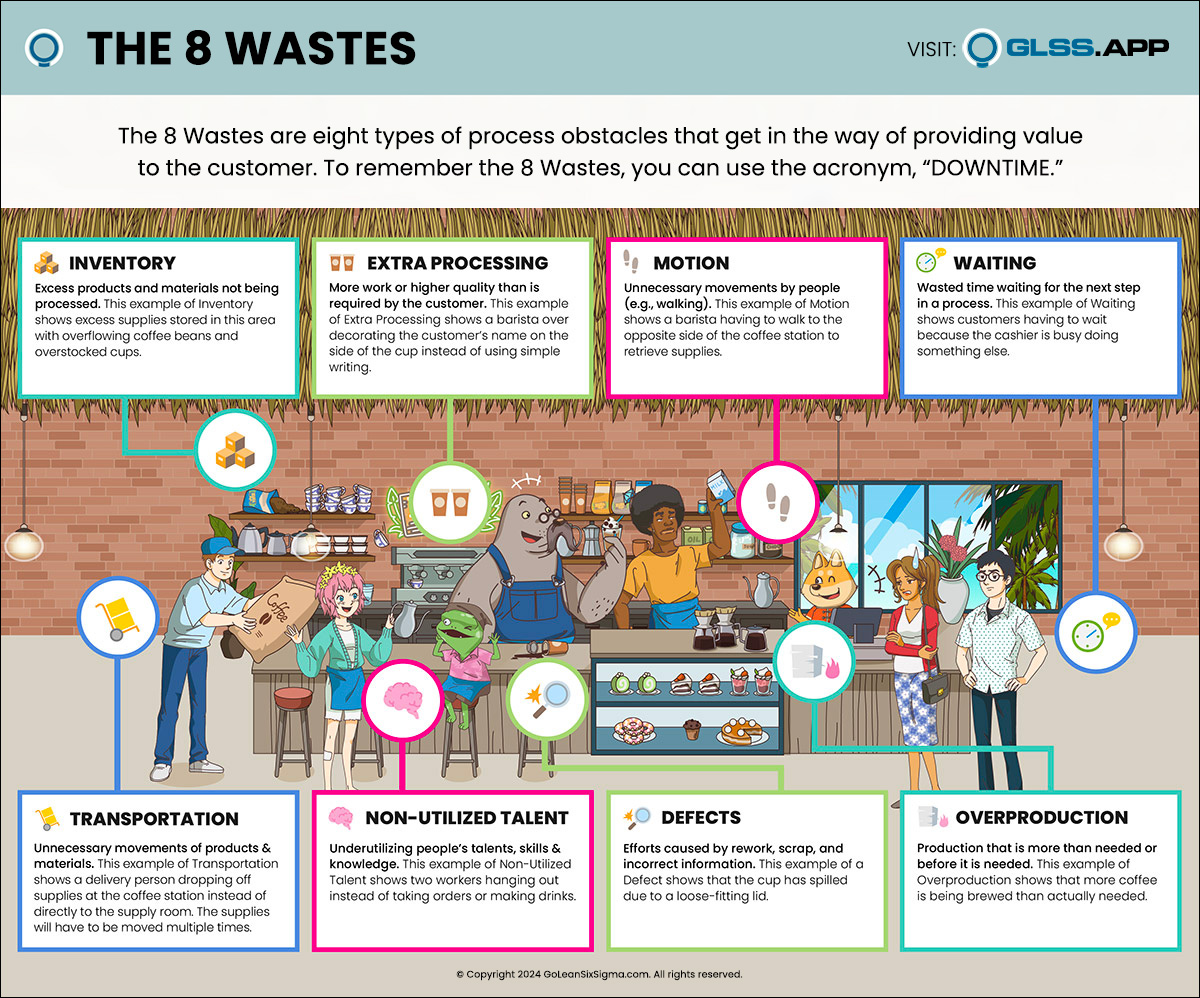

Let’s look at this system problem from a Lean standpoint. We can agree that data helps understand and diagnose problems. Lean practitioners know that collecting data takes time and resources so we try to ensure that the data has a purpose and can answer key questions or hypotheses. We also use good data collection planning techniques to evaluate the value of data compared to the resources to collect.

How Much Time Is Spent Testing?

Most states require a minimum of 180 days of student instruction per year. The focus indeed is intended to be student instruction but the number of tests and the time spent preparing for tests has been increasing in recent years. Furthermore, students are expressing that they are all tested out. The opt-out movement is a response to student voiced concern over testing stress.

Testing time has tripled in grades 3-5 between 2012 and 2014.

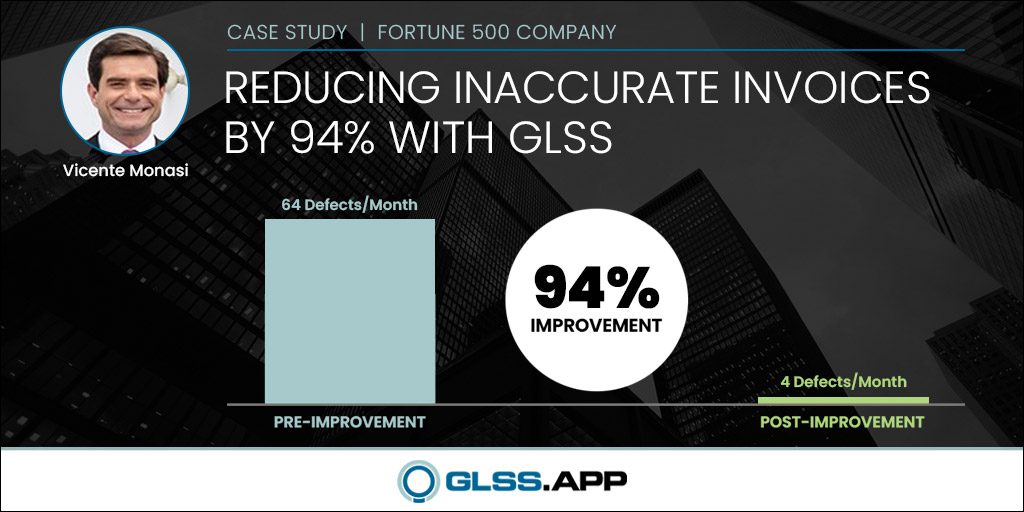

Testing time has tripled in grades 3-5 between 2012 and 2014. A Study of Assessment Use in Colorado Districts and Schools from November 2014 finds that seat time – time to prepare and take state and local assessments – for a 4th grader, 9-10 years old, is 72 hours or 12 days. That’s 6.7 percent of the school year spent collecting the data!

Where’s the Value-Add?

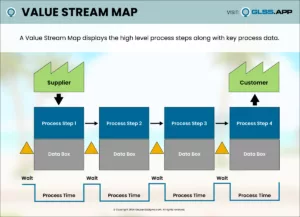

The time to collect the test data could be justified if it had a strong contribution to student learning and academic achievement. That’s where the state testing process gets more complex.

State assessments are primarily used to allocate state and federal education funding. The results take greater than 6 months to return to the schools, teachers and parents. The assessment results are delivered once the next school year has begun. That practice alone makes the data less relevant to improve student performance because it’s not timely to take action to improve. The Lean practice of providing fresh data on performance is not evident here.

The results take greater than 6 months to return to the schools, teachers and parents.

Most local assessments produce results in 1-2 weeks from the taking of the test. Those test results can be used to redirect learning for an individual student to improve. Therefore, local tests can be considered value adding to student achievement.

Students Opt Out

When students opt out of state testing, the time spent to prepare and take the assessments are wasted and that’s not value added to student outcomes. It seems appropriate that administrators and legislators should consider whether the time spent to collect common core standardized test results is really improving the outcome of student performance.

In conclusion, while data is good, too much of it can be a bad thing.

In conclusion, while data is good, too much of it can be a bad thing. In the case of state mandated standardized testing, it’s purpose is limited by the lagging release of results which don’t make an impact on student performance.