Circa 2005, one of our employers, who had adopted Lean in the early 90s, decided to make Six Sigma mandatory for salaried employees. As a Lean zealot, I went kicking and screaming down the path of my Green Belt Certification. The only thing that made the experience fun was that a dear friend and colleague was on the project with me.

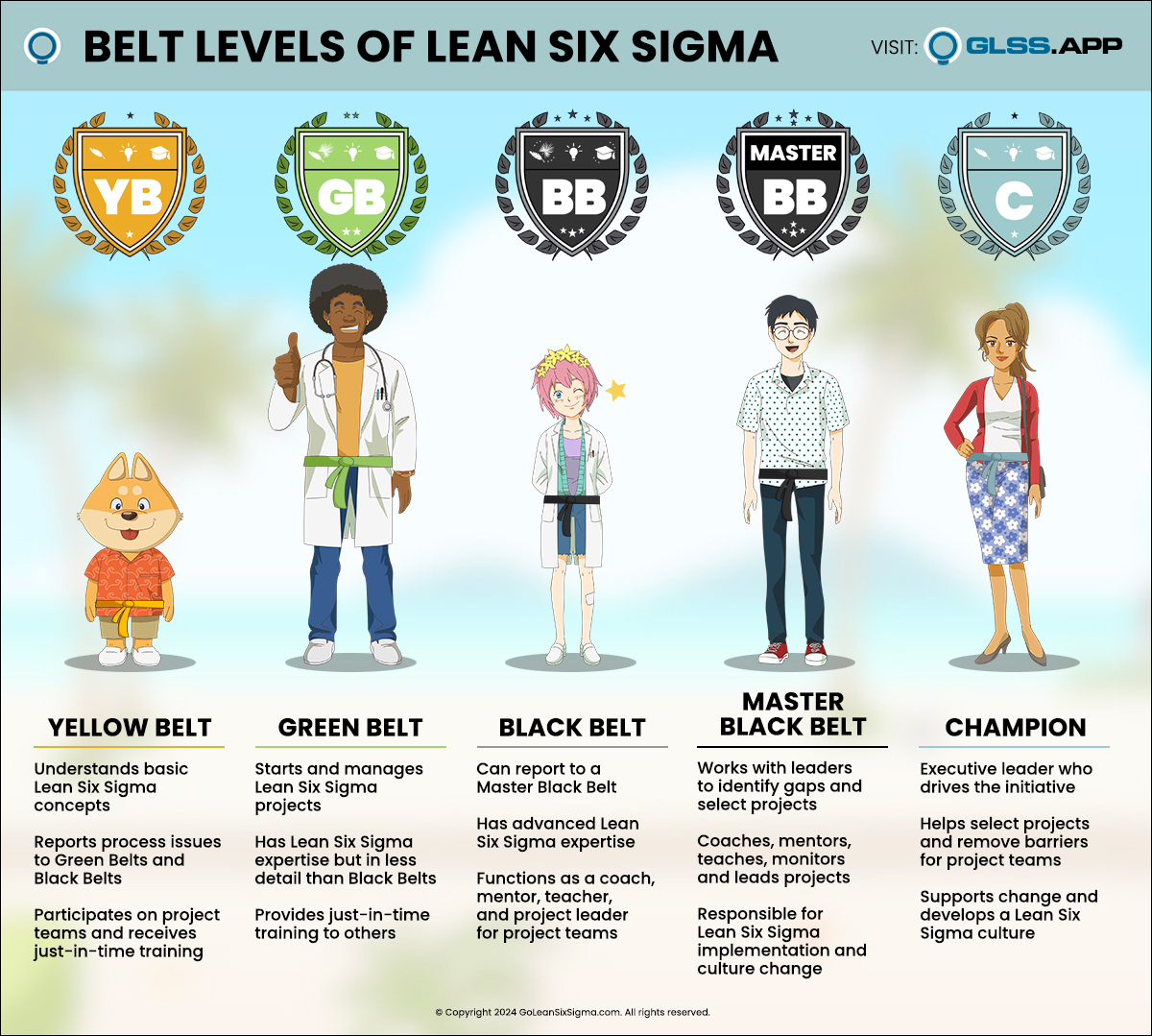

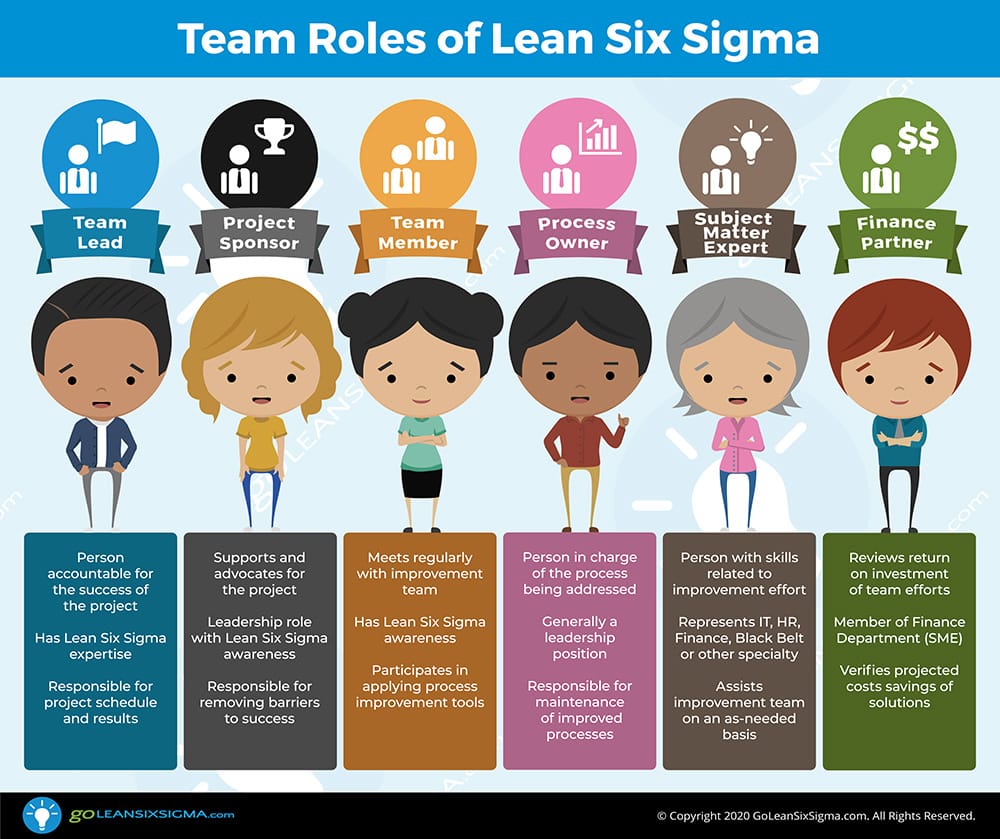

But, I digress. We went on a witch hunt to find a project to yield savings. During the process, we had the guidance of an amazing Master Black Belt. Our leadership team, on the other hand, was still finding their way—much like me. We put together our project charter in spite of looming questions and resistance.

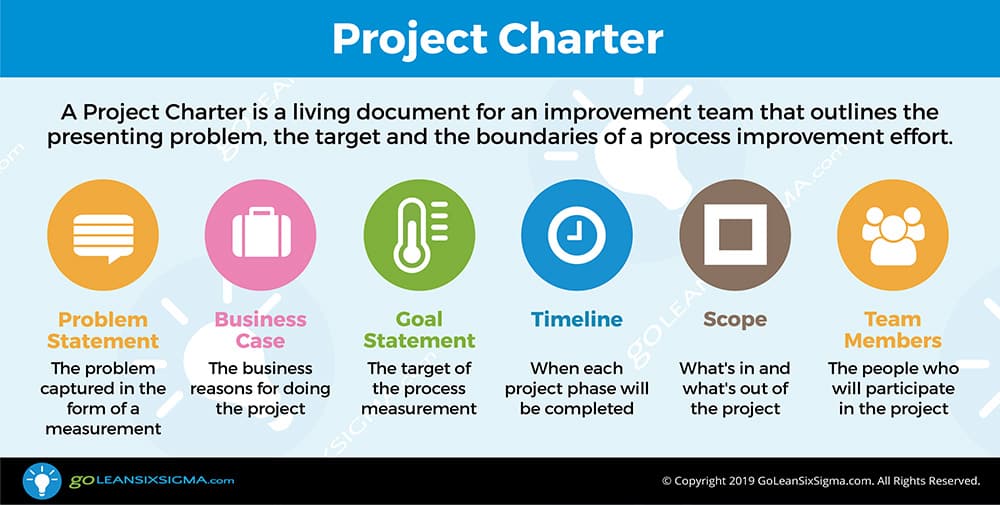

Starting With a Project Charter

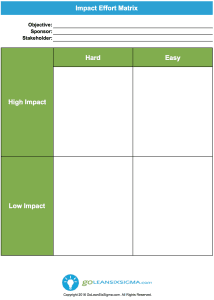

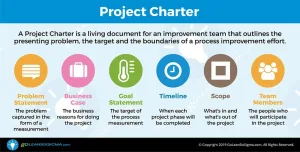

The project charter serves as a roadmap where Stakeholders agree on the direction of the problem-solving effort. The charter includes essential information for determining resources, goals, objectives, risks, budget, and decision-making authorities.

Projects are finite with projected start and end dates, an agreed-upon scope of work, and a cross-functional team assigned to establish a high-level implementation plan. The project charter, however, is not the detailed project plan. Simple enough, right?

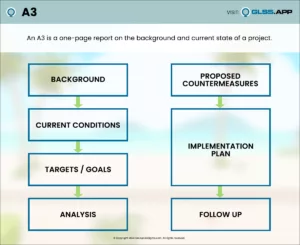

This seemingly simple contract was easy to draft yet difficult to gain buy-in on. For me, it was unlike the A3 process where the process of Catchball—where leadership collaborates with frontline employees on direction—felt more like a waltz. While we were essentially conducting a similar process to seek buy-in and evaluate the thought process, the approach felt extremely rigid and cold. It felt disjointed and disconnected. Why was this?

Reflections on a Green Belt Project

I didn’t pause to better understand how I felt during this experience. At the time, I simply wanted to finish the task at hand which was to complete the first level of certification. The problem was that by this point in my career I had experienced a few major Lean transformations in different locations with different leaders. I wasn’t interested in simply “doing a project.”

It would be years before I fully understood the significance of this experience and the missed opportunity. Looking back, I realize my reaction was because the project didn’t feel like meaningful work to me. Certainly, the problem required a solution. But my experience was that transformation work was chock full of meaning and deep engagement.

Given my competitiveness and will to succeed, we pushed through the Green Belt project and exceeded our projected savings. The scope of the project expanded so it ended up being more of a Black Belt level project. We were satisfied to have completed the Green Belt Certification, and our management team was excited that our project helped them meet their savings target.

I share this story to invite you to expand your understanding of human behavior in any effort, and to seek the deeper meaning of the projects in which you engage for yourself and the user.

Exploring the Deeper Meaning

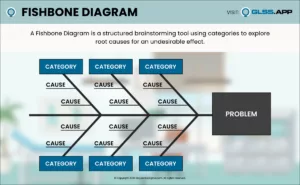

How does one do that? “Expand your understanding of human behavior”? There are many things we can do to advance our understanding of human behavior. However, first we need to understand how to observe and make sense of what’s at hand. Below are four approaches to keep in mind for understanding the human factor:

1. Tapping Into Tribal Knowledge

This may include tapping into local groups, leveraging extended networks, and engaging in Catchball to understand if our perception of truth matches that of the frontline’s. This is key since I’ve seen project charters that suffer from “inattentional blindness”—when our eyes are open but we necessarily “see” what’s in front of us.

We can avoid this if we don’t depend solely on deductive reasoning—looking at a spreadsheet, seeing facts, developing a hypothesis, and acting on it.

2. Using Openness When Reasoning

The same goes for the type of reasoning where we actively observe the process and use our observations to create generalized conclusions. We remain open to gathering conclusions and forming hypotheses to be tested before coming up with a solution.

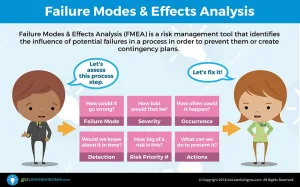

This is vital as many project charters force solutions with biased reasoning and have not fully explored the potential problem and made sense of the situation at hand.

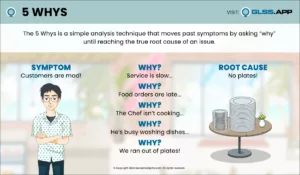

3. Asking the Right Questions

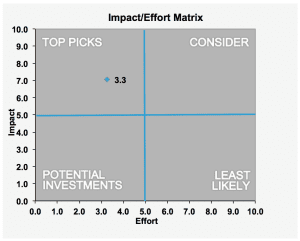

Questions we ask might reveal that it isn’t the right project to work on. In my experience, mobilizing a search party to seek out different perspectives from different areas can help. They enable us to test out multiple hypotheses and the wisdom of the crowd. This creates diverse scenarios to challenge our current assumptions, trust seasoned intuitions, and broaden our perspective.

4. Leading With Exploration—Not Solutions

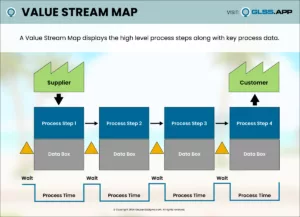

It’s critical that we lead with exploration, not with solutions. We should seek to understand the human behavior and the data as well as the context in which it’s applied. In order to see the big picture and the existing possibilities, it’s crucial to talk to customers and even competitors. Don’t ignore what doesn’t fit. Have a bias towards understanding.

Using the Cynefin Framework to Think Broadly

Since one of the challenges is to open up the problem-solving thought process, the Cynefin Framework offers a helpful model. It is a cognitive decision-making approach that helps managers identify their own perceptions when trying to understand human behavior. Developed by David Snowden, his work unveiled a better understanding of the domains in which we operate to solve problems.

For example, in a linear world, where clear solutions are presented and the cause and effect is known, the notion of scaling best practices becomes legitimate. However, in a nonlinear, complicated domain—such as aspects of the production system or complex problems—it no longer works.

Snowden warns that those who adopt best practices with a copy-and-paste mentality to complicated domains are actually most vulnerable to creating chaos. One should work hard to understand complicated domains and only in selective conditions assume the process is clear and linear in order to avoid chaos.

What can we take away from the Cynefin Framework? The pitfalls to good problem solving include gathering insufficient information, yielding to group think, reacting to the wrong signal or even reacting too soon. Project charters require working toward holistic understanding and assessment of the situation. This helps ensure charters contain unbiased opinions and promote good, complex problem solving. The key is to avoid solution-based best practices.

Engaging People

In the Green Belt project story, I mentioned that getting buy-in was a challenge, which is the case most of the time. ‘Buy-in’ has a selling connotation. The person(s) seeking the buy-in needs to “sell” their case to gain support or approval.

I realized that in my experience with transformations, and when using the Catchball process, the feeling was one of engagement and being a part of something bigger than the process of improvement. The transformations provided room for cultural changes as well as personal and professional development.

During the project charter phase, the team works to gather an effective direction for the implementation. This is the time to drive a high level of engagement regarding the project scope and implementation plan.

IDEO as an Engagement Example

Several years ago, IDEO, then a small company, was featured on the news show 60 Minutes. The story featured this company’s rapidly short-cycled product design from ideation to implementation. More intriguing than the rapid prototyping was how the teams worked together to drive heightened innovation and engagement.

This wasn’t simply about teamwork or team dynamics. It was about leveraging the best of what each person brought to the project—their unique genius. You might be thinking, “What does this have to do with Lean?” Or better yet, “I don’t design products.” Hang in there with me.

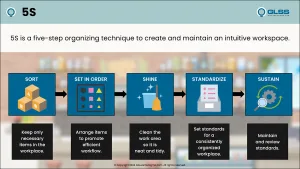

This framework is called Design Thinking. It has been around for some time and many of you may be familiar with it. If you’re unfamiliar, Design Thinking is about solving complex problems in a user-centric way ensuring great experiences and outcomes for the user. It is both an ideology and methodology.

Design Thinking takes the approach used by product designers applied to other complex problems. There are five phases: Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype and Test. The Design Thinking process is iterative—not linear—much like PDCA and DMAIC.

In terms of my Green Belt experience, it would have been amazing if during that process I had a safe way to express my desire to engage in a more meaningful way rather than treating the process as a task or project to be completed. Would I have been able to address my challenges when seeking buy-in?

We have a chance—a responsibility—as change agents to give more consideration to users to create a level of engagement that drives more effective problem solving.

The Empathize Phase of Design Thinking

Let’s dive into the first phase of Design Thinking, Empathize. This involves the following:

- Putting the user experience first

- Learning about their pain points

- Learning about their desired outcomes of a product or experience

- Getting to know them; understanding them on a physiological and emotional level

This allows you to create effective solutions to meet these needs. It also requires that we toss out our assumptions and focus on real user insights. This requires us as change agents to constantly rethink what we’ve done before.

Back to the project charter and what Design Thinking brings to the table. As showcased by IDEO, the trick is to invite other minds to the problem-solving table up front. The charter is where you determine the team and identify subject matter experts. Use this document as a means to invite the “unique genius” of wide-spread Stakeholders to the table. And then learn about their experience.

The Project Charter Today—A Case Study

I work with a small company, $20M in revenue, with 100% transactional operations. The scope of my responsibilities includes an operational growth strategy and implementation support. There are fewer than 50 employees. All “normal” Kaizen work has been deprioritized to focus on business continuity planning such as preparing for remote work for essential and critical path employees; evaluating every possible scenario to keep people employed through this crisis—all while meeting compliance criteria.

In an environment where CEOs, managers, and employees are stressed beyond measure, sense-making and empathizing are critical to helping people push past their fears and concerns to focus on work, improvements, and new procedures. Honestly speaking, in order to better serve them, I’ve had to institute “mental break blocks” to manage my concerns as a business owner as well as the health risks that come with being in their office.

The project charter provided the structure needed to limit irrational and reactive decision making and to arrive at solutions to the organizational challenges of this crisis. However, without considering people, human behavior, and the domains where people operate first, the organization would not have been able to align with a plan to extend business.